- Pronunciation:

- \ˈmith\

- Function:

- noun

- Etymology:

- Greek mythos

- Date:

- 1830

1 a: a usually traditional story of ostensibly historical events that serves to unfold part of the world view of a people or explain a practice, belief, or natural phenomenon b: parable , allegory

2 a: a popular belief or tradition that has grown up around something or someone ; especially : one embodying the ideals and institutions of a society or segment of societymyth of individualism — Orde Coombs> b: an unfounded or false notion

3: a person or thing having only an imaginary or unverifiable existence

4: the whole body of myths

Judging from M-W's definition above, our menagerie of beings, from the aswang to the nuno sa punso and everything else in between would definitely fall under the category of things with "imaginary or unverifiable existence."

I don't have any problem with that. Social norms agree that the belief of the majority should preside over the unfounded assertions of the few. In this day and age, very few people actually believe in the existence of the aswang, the mangkukulam, etc., and even fewer people claim to possess evidence pointing to the truth of these beings' existence, even in some of the Philippine 's remotest provinces. As the masses become more and more educated, people began to question old beliefs, superstitions and folk lore. A lot go by the dictum that "seeing is believing."

Careful, rational observation and studies have unclouded a lot of myths in the past few hundred years. Take the disease Malaria for example. In the olden times, people thought that Mal Aria, which literally means "bad air" in latin, was caused by the foul smell coming from stagnant bodies of water like moats or swamps. The debilitating chills and fever caused by Mal Aria afflicted mainly those people who live near such bodies of water leading to the classic cause=effect assumption that the foul smelling air itself causes the disease. It took the invention of the microscope for us to determine that microbes carried by mosquitoes breeding in stagnant pools were the real culprit. However the name "Mal Aria" has stuck, rendered a misnomer by the advances in medical science.

Creating assumptions from observable natural phenomena is a natural cognitive function. Much like a mental version of Pavlov's conditional reflex theory which essentially states that the presence of two variables preceding a corresponding effect can cause a subject to respond the same way in case one of the two variables (the dependent one) is removed. In short, we reduce everything to two things: cause and effect. Thus, the repeated presence of a presumed cause before a presumed effect will bolster out belief that the presumed cause is also the logical cause.

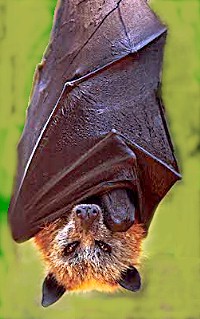

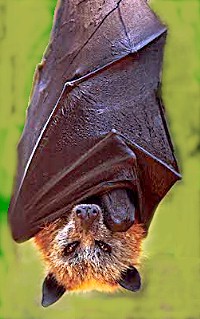

This is why preconceived notions play a vital role in the shaping or propagation of a myth. Take for example the Philippine Flying Foxes or Giant Fruitbats, some of which reach 5 foot wingspans. In a place were both the Bat (a reality) and the Manananggal (A myth) exists, it's fairly easy to mistake the reality for the myth. Factor in the element of dusk or darkness (where it's easy to mistake a large bat for anything sinister) and you have the perfect recipe for a folk horror story.

But would you do if you find someone who has supposedly seen a manananggal, and that person is say, reputable, has good knowledge of the fauna in his area, has good eyesight, and seeks no publicity whatsoever? Chances are you won't believe him but you will investigate further. Have you covered all the possibilities? Have you checked if he was inebriated at that time? Does schizophrenia run in his family? Is the area at the foot of an elevated hang-glider spot? Did someone lose a big umbrella that e vening? Once you've satisfied all these questions, and more and yet the story stands on its own you have an Anomaly. Something that happened without dispute but can't be explained in orthodox scientific terms.

vening? Once you've satisfied all these questions, and more and yet the story stands on its own you have an Anomaly. Something that happened without dispute but can't be explained in orthodox scientific terms.

Having something anomalous is an invitation to come up with all sorts of crazy ideas and that's the fun part. what if these things really do exist? What if being a manananggal or an aswang is simply a malady unknown to science? What if Science is totally wrong and we really have a thriving menagerie of elementals or demons or monsters in our backyard? What if our age-old folk tales and belief in the occult and the paranormal is merely a form of mass hysteria, subconscious social control or plain uneducated misinterpretation? What is both science and superstition is wrong and there's a third, independently verifiable point of view on the matter? What then?

One thing is certain. Some myths or mythical creatures, however fantastical they sound, could have been derived from some sort of precursor reality which has been morphed, modified and distorted by society over time to fit the prevailing socio-eco-poli-cultural context. The concept of the "Aswang" can be explained in anthropological terms as a form of social control and a collective memory of the Spaniards' indictment of things indigenious or "pagan" in their attemps to spread Christianity in these islands since the 16th century.

Our fear of the unknown and the sick could also be partly responsible for the "aswang" concept. Take the case of the disease known as TDP or Torsion Dystonia of Panay. Victime of this neuro-muscular disease, to the uninitiated, would look like someone trying to morph or expel their inner demons. There is nothing demonic about this disease which is endemic to the island of Panay but somehow, the grotesque symptoms of the disease which includes involuntary muscular contractions and profuse saliva production perfectly fits the concept of the anthropid "aswang" our parents or grannies or yaya from the provinces have been talking about every Good Friday or Halloween season.

This theory, however, does not explain the origins of the other "forms" of the Aswang which is known to take the shape of a huge pig, bird, cat or dog. Most people who reported aswang encounters reported seeing them in this configuration, like in the case of the boy who survived an alleged Aswang attack in 2004.

People can make all sorts of claims but they won't be able to establish the veracity of their sighting unless they have a photo or DNA-rich hair strand to back their claims. Conversely, people can't just debunk these stories outright without offering evidence that will eliminate the possibility of a hoax or mistake beyond reasonable doubt.

Just as relying too much on science is an invitation to be arrogant, relying too much on superstition and myth makes a society utterly backward and ignorant. A learned man trained in the ways of science sometimes finds it easy to be smug and dismiss the mythical and the supernatural as a fabrication, misidentification or plain lunacy. I personally believe we must temper our reasoning with a sense of wonder and an open mind to ask "What if...?" in the face of strange questions that science cannot readily answer. As Jordan Clark* (director of the documovie Aswang: A journey into Myth) puts it, "I can't say that the person who claims to see an aswang is mistaken since I was not there." I'd say that's admirable for an outsider looking in to find the truth behind the lingering myth.

*Jordan Clark is currently in Panay Island filming his full length documentary about the "Aswang" phenomenon in the Philippines

2 a: a popular belief or tradition that has grown up around something or someone ; especially : one embodying the ideals and institutions of a society or segment of society

3: a person or thing having only an imaginary or unverifiable existence

4: the whole body of myths

Judging from M-W's definition above, our menagerie of beings, from the aswang to the nuno sa punso and everything else in between would definitely fall under the category of things with "imaginary or unverifiable existence."

I don't have any problem with that. Social norms agree that the belief of the majority should preside over the unfounded assertions of the few. In this day and age, very few people actually believe in the existence of the aswang, the mangkukulam, etc., and even fewer people claim to possess evidence pointing to the truth of these beings' existence, even in some of the Philippine 's remotest provinces. As the masses become more and more educated, people began to question old beliefs, superstitions and folk lore. A lot go by the dictum that "seeing is believing."

Careful, rational observation and studies have unclouded a lot of myths in the past few hundred years. Take the disease Malaria for example. In the olden times, people thought that Mal Aria, which literally means "bad air" in latin, was caused by the foul smell coming from stagnant bodies of water like moats or swamps. The debilitating chills and fever caused by Mal Aria afflicted mainly those people who live near such bodies of water leading to the classic cause=effect assumption that the foul smelling air itself causes the disease. It took the invention of the microscope for us to determine that microbes carried by mosquitoes breeding in stagnant pools were the real culprit. However the name "Mal Aria" has stuck, rendered a misnomer by the advances in medical science.

Creating assumptions from observable natural phenomena is a natural cognitive function. Much like a mental version of Pavlov's conditional reflex theory which essentially states that the presence of two variables preceding a corresponding effect can cause a subject to respond the same way in case one of the two variables (the dependent one) is removed. In short, we reduce everything to two things: cause and effect. Thus, the repeated presence of a presumed cause before a presumed effect will bolster out belief that the presumed cause is also the logical cause.

This is why preconceived notions play a vital role in the shaping or propagation of a myth. Take for example the Philippine Flying Foxes or Giant Fruitbats, some of which reach 5 foot wingspans. In a place were both the Bat (a reality) and the Manananggal (A myth) exists, it's fairly easy to mistake the reality for the myth. Factor in the element of dusk or darkness (where it's easy to mistake a large bat for anything sinister) and you have the perfect recipe for a folk horror story.

But would you do if you find someone who has supposedly seen a manananggal, and that person is say, reputable, has good knowledge of the fauna in his area, has good eyesight, and seeks no publicity whatsoever? Chances are you won't believe him but you will investigate further. Have you covered all the possibilities? Have you checked if he was inebriated at that time? Does schizophrenia run in his family? Is the area at the foot of an elevated hang-glider spot? Did someone lose a big umbrella that e

vening? Once you've satisfied all these questions, and more and yet the story stands on its own you have an Anomaly. Something that happened without dispute but can't be explained in orthodox scientific terms.

vening? Once you've satisfied all these questions, and more and yet the story stands on its own you have an Anomaly. Something that happened without dispute but can't be explained in orthodox scientific terms.Having something anomalous is an invitation to come up with all sorts of crazy ideas and that's the fun part. what if these things really do exist? What if being a manananggal or an aswang is simply a malady unknown to science? What if Science is totally wrong and we really have a thriving menagerie of elementals or demons or monsters in our backyard? What if our age-old folk tales and belief in the occult and the paranormal is merely a form of mass hysteria, subconscious social control or plain uneducated misinterpretation? What is both science and superstition is wrong and there's a third, independently verifiable point of view on the matter? What then?

One thing is certain. Some myths or mythical creatures, however fantastical they sound, could have been derived from some sort of precursor reality which has been morphed, modified and distorted by society over time to fit the prevailing socio-eco-poli-cultural context. The concept of the "Aswang" can be explained in anthropological terms as a form of social control and a collective memory of the Spaniards' indictment of things indigenious or "pagan" in their attemps to spread Christianity in these islands since the 16th century.

Our fear of the unknown and the sick could also be partly responsible for the "aswang" concept. Take the case of the disease known as TDP or Torsion Dystonia of Panay. Victime of this neuro-muscular disease, to the uninitiated, would look like someone trying to morph or expel their inner demons. There is nothing demonic about this disease which is endemic to the island of Panay but somehow, the grotesque symptoms of the disease which includes involuntary muscular contractions and profuse saliva production perfectly fits the concept of the anthropid "aswang" our parents or grannies or yaya from the provinces have been talking about every Good Friday or Halloween season.

This theory, however, does not explain the origins of the other "forms" of the Aswang which is known to take the shape of a huge pig, bird, cat or dog. Most people who reported aswang encounters reported seeing them in this configuration, like in the case of the boy who survived an alleged Aswang attack in 2004.

People can make all sorts of claims but they won't be able to establish the veracity of their sighting unless they have a photo or DNA-rich hair strand to back their claims. Conversely, people can't just debunk these stories outright without offering evidence that will eliminate the possibility of a hoax or mistake beyond reasonable doubt.

Just as relying too much on science is an invitation to be arrogant, relying too much on superstition and myth makes a society utterly backward and ignorant. A learned man trained in the ways of science sometimes finds it easy to be smug and dismiss the mythical and the supernatural as a fabrication, misidentification or plain lunacy. I personally believe we must temper our reasoning with a sense of wonder and an open mind to ask "What if...?" in the face of strange questions that science cannot readily answer. As Jordan Clark* (director of the documovie Aswang: A journey into Myth) puts it, "I can't say that the person who claims to see an aswang is mistaken since I was not there." I'd say that's admirable for an outsider looking in to find the truth behind the lingering myth.

*Jordan Clark is currently in Panay Island filming his full length documentary about the "Aswang" phenomenon in the Philippines

No comments:

Post a Comment